Lab 5: Git/GitHub Tutorial#

GitHub is a code hosting platform for version control and collaboration. It lets you and others work together on projects from anywhere.

GitHub essentials#

Before we head to the basics, create/log in your GitHub account.

Repositories#

A repository is usually used to organize a single project.

Repositories can contain folders and files, images, videos, spreadsheets, and data sets – anything your project needs.

Often, repositories include a README file, a file with information about your project written in the plain text Markdown language. A Markdown language cheat sheet: https://www.markdownguide.org/cheat-sheet/

Now let’s practice!

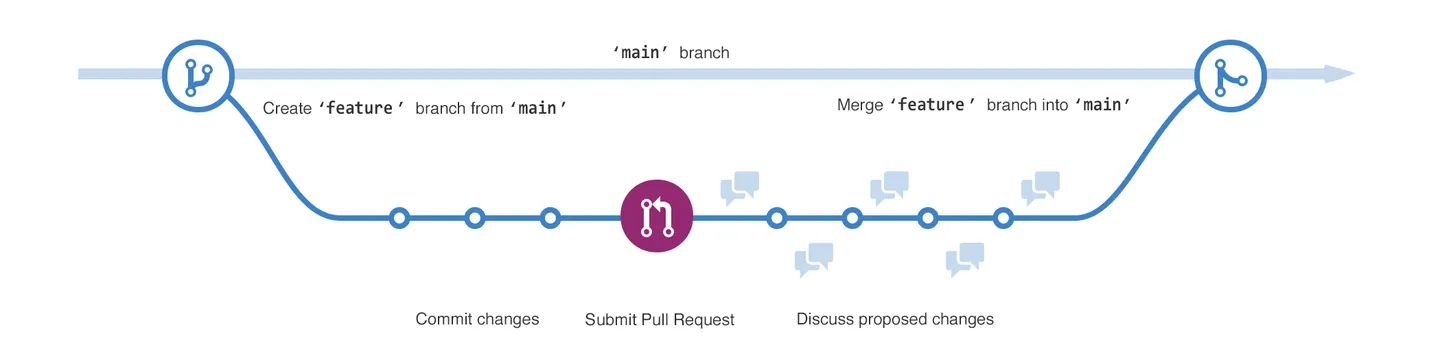

Branches#

Branching lets you have different versions of a repository at one time.

Your repository has only one branch named

mainby default, but you can create additional branches off ofmainin your repository. You can use branches to have different versions of a project at one time. This is helpful when you want to add new features to a project without changing the main source of code.The work done on different branches will not show up on the

mainbranch until you merge it. You can use branches to experiment and make edits before committing them tomain.

Practice: Create readme-edits branch.

Commits#

When you created a new branch in the previous step, GitHub brought you to the code page for your new

readme-editsbranch, which is a copy ofmain.You can make and save changes to the files in your repository. On GitHub, saved changes are called commits.

Each commit has an associated commit message, which is a description tha captures the history of your changes so that other contributors can understand what you’ve done and why.

Practice: Edit the README.md file and commit changes. Now this branch should be containining content that’s different from main.

Pull Requests#

Now that you have changes in a branch off of

main, you can open a pull request.Pull requests are the heart of collaboration on GitHub. When you open a pull request, you’re proposing your changes and requesting that someone review and pull in your contribution and merge them into their branch. Pull requests show diffs, or differences, of the content from both branches. The changes, additions, and subtractions are shown in different colors.

As soon as you make a commit, you can open a pull request and start a discussion, even before the code is finished. By using GitHub’s

@mentionfeature in your pull request message, you can ask for feedback from specific people or teams.

Practice: Create a pull request. Now your collaborators can review your edits and make suggestions.

Merging your pull request#

In this final step, you will merge your

readme-editsbranch into themainbranch. After you merge your pull request, the changes on yourreadme-editsbranch will be incorporated intomain.

Use Git/GitHub with Jupyter Notebook#

Add a notebook to the GitHub repository#

Copy the highlighted HTTPS repository URL, and clone the GitHub repository on our machine by running following on the terminal:

git clone https://github.com/usrname/repositoryname.git. It will create lab05 directory on our machine which is linked tolab05repository on Github.Let’s push some notebooks to the repository. We copy two notebooks to the directory where we cloned projectA repository,

cp /some/path/analysis1.ipynb /path/of/lab05/.To push

analysis1.ipynbto GitHub, we first need to tell local git client to start tracking the file usinggit add analysis1.ipynb(If you want to upload more than one notebooks, instead you can update the repository by enter the folder of the github repositary that you want to update, then typegit add .). You can check which files are being tracked withgit status.Now let’s commit the changes,

git commit -m "Adds customer data analysis notebook"Let’s push this commit to GitHub:

git push

Integrate the remote changes to your local directory#

git pullIf you have made local changes to the directory, you need to commit your changes or stash them before you merge. You can’t merge with local modifications.

Three options#

Commit the change using:

git commit -m "My message"Stash the change using

git stash, you can do the merge, and then pull the stash:git stash popDiscard the local changes using

git reset --hardfor all changes orgit checkout filenamefor a specific file.

Motivation for git#

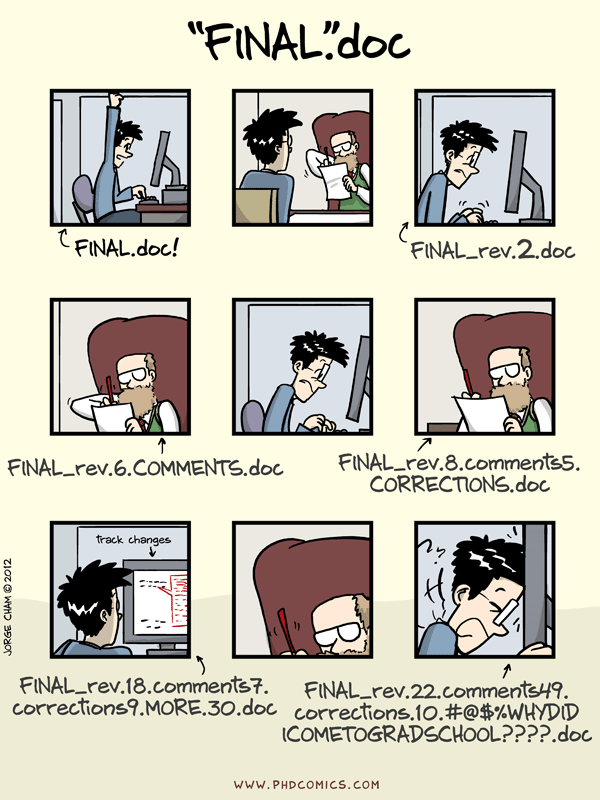

Good practice in programming project management requires a version control system.

Old school techniques are usually bad.

Version filenames is a disaster.

mythesis_v1.tex,mythesis_v2.tex,mythesis_last_v3.texcreates clutter

Filenames rarely contain information other than chronology

Parallel independent changes super hard to keep track of

Did you finally notice a problem in v119 that has been around for a while, but you have no idea where the error was introduced?

Sharing files with others is a disaster.

Emailing files sucks — only magnifies the problems above

Track changes feature Google Docs or Word — not so useful for anything complex

Disaster recover is a disaster.

Oh F#@K! Did I just overwrite all my work from last night??!!!?

Modern version control techniques are usually great.

Modern tools to promote collective intelligence.

Automated history of everything

not just files, but whole projects with folders and subfolders

who, what, when, and (most important) why

Automated sharing of everyone’s latest edits

no more emailing files around

Easier disaster recovery with distributed VCSes like Git or Mercurial (see later)

Support for automated testing (we’ll cover this in future lectures)

Infinite sandboxes for clutter-free, fear-free experimentation

this is where Git especially shines – main topic today

CAVEAT 1: All of this works best with plain text files

CAVEAT 2: All of this works best with a highly modular file structure

The git feedback effect:

Using git encourages positive changes to your workflow.

And making your workflow more git-friendly will make your work better overall.

Brief history of version control#

Local Version Control

Mainly just reduced clutter and automated tracking of chronology…

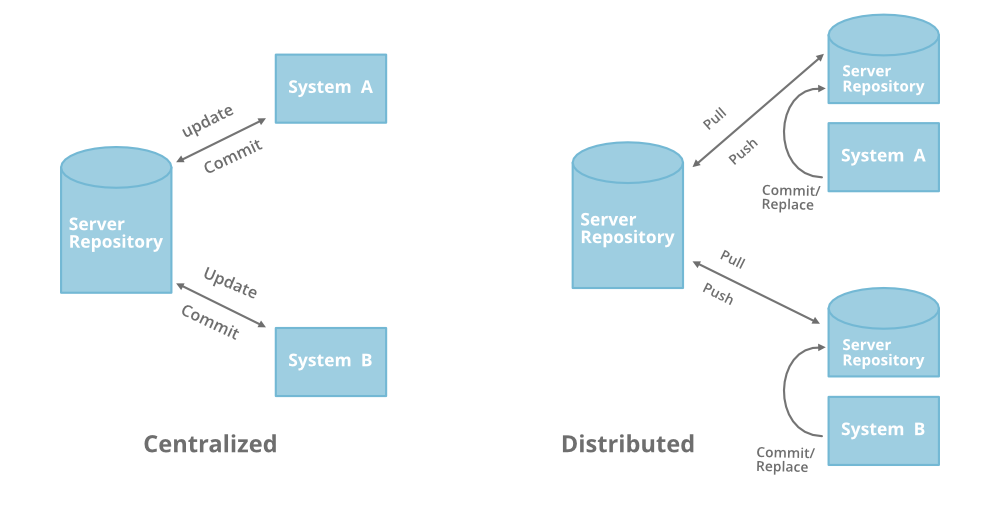

Centralized Version Control

Allows group work on the same files…

Single point of failure — there is only a single “real” repository

Backing up is a separate process

File locks — create “race conditions” for committing changes to that “real” repository

What if you lose internet?

Branching is cumbersome, so people don’t do it (and have trouble reconciling disparate histories when they do)

Distributed Version Control

Resolve most of the above issues…

Many separate and independent repos; all are “first-class” citizens

Can make commits locally even without internet…

…but can transfer history and information between repositories

Branching is lightweight and easy (mainly in Git)

Core concepts in git#

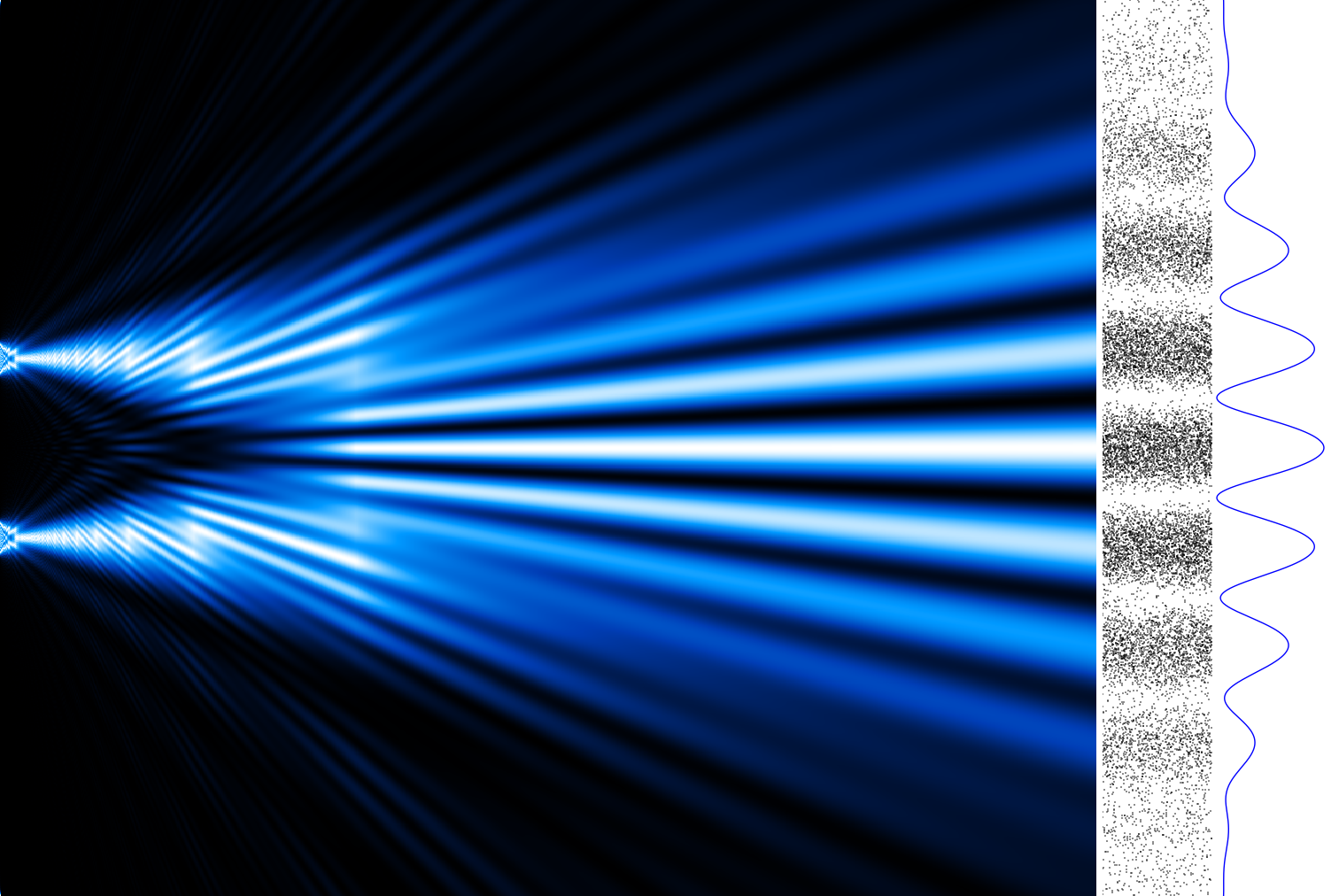

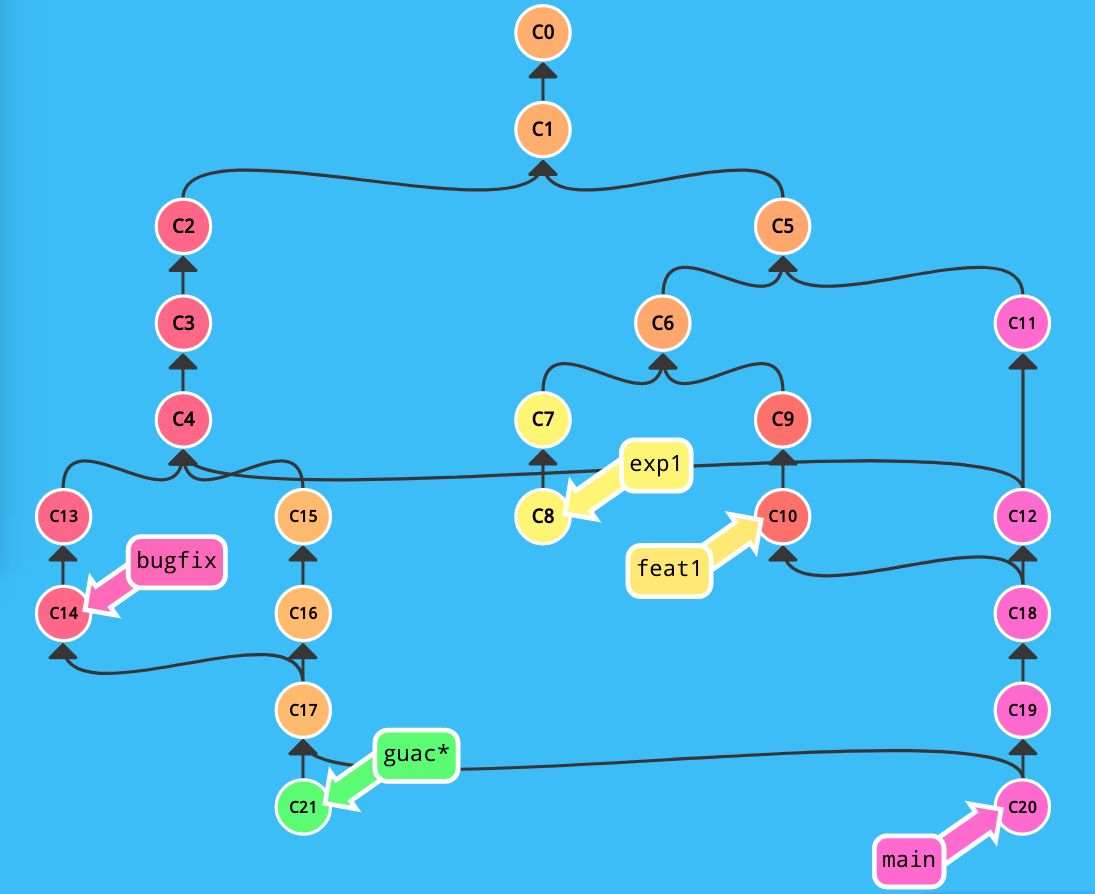

Branches and DAGs

A DAG is a directed acyclic graph linking together a sequence of tasks.

Let’s calibrate people’s intuitions about git terminology: how many branches are in this DAG?

Best way to get comfortable conceptually with git branching is to see it in action.

So let’s do an exercise…

Things to keep in mind during our exercise

Just a quick tour

Some git operations are of a “send it out” variety, while others are of a “bring it in” variety

important to keep straight which are of which flavor

Some git operations are repo-wise, while others are branch-wise

Your git branching sandbox

Open a browser to this URL: https://learngitbranching.js.org/?NODEMO

Other resources for git: